Inside Liverpool's most intriguing pub strip: "Dry January? Get a cream for that, lad"

While most of the city embarks on another joyless January, Great Charlotte Street's afternoon regulars are definitely, and gloriously, doing it their way. And all for £2.30 a pint.

I started the year with a terrible mistake. I went for a swim off Leasowe beach, swept away with the hype of boosted serotonin and an immune system invincible to all known pathogens. It was abhorrent. A week later and I’m only just enjoying the sensation of fully functioning thighs again. As we drove home, the DJ on 6Music was ordering us to walk everywhere: “Get fit for life in 25,” he barked. “I’ve started Veganuary with a delicious tomato curry.”

Our neighbours had previously cancelled a night out this weekend. “Dry January, innit.” They texted. As if the mere suggestion of a small Albariño would elicit a dawn raid from the Operation Misery squad. Come to think of it, I’m quietly disappointed my friend had texted at all, as she was clearly in breach of her self-imposed Christmas digital detox. I might get my Quink ink out and drop her a scroll after I’ve written this.

Stung into rebelling against a rising tide of moral asceticism, I know what I have to do. An immersion in the warm embrace of Great Charlotte Street is the only vaccination I need to survive the bleak midwinter.

The city centre is dead. Caught off guard between two sudden snowstorms, its streets have a dazed and defeated look. The fireworks are through, and it’s time to get back to business, but Liverpool’s just hit the snooze button and turned over for ten more minutes.

A man in the foyer of the Playhouse scrubs the last remains of Christmas away while another, outside, crouches in a flurry of sleeping bags, holding up a sign that testifies, uselessly, to his hunger and cold.

Great Charlotte Street used to be here. Once upon a time it sliced right through from Central Station to St George’s Hall. The arrival of St John’s Precinct in the 60s stopped it in its tracks. It’s tempting to wonder what its role would be if it was still allowed to fully unfurl. Another great streetscape buried beneath the bright new future we’re still holding our breath for.

But talk of Great Charlotte’s death is, thankfully, exaggerated. Despite its cruel and unnecessary cauterisation, there is no doubt that, on this first Monday of the new year, this tiny stretch of street is the only proof that there is life on planet Liverpool. John Lewis and the Metquarter might be echoey and empty but, unseen by most of us, the real motor of our city chugs on.

I walk past Wetherspoons’ Richard John Blackler, named after the founder of this block’s magnificent department store - although, at two in the afternoon, it’s doing great business. I’m grateful that, at least, the chain has retained the store’s fine ashlar masonry, all that’s left of this grand old bird, once considered the Macy’s of Britain. But it’s a Wetherspoons, and I’d rather cryogenically freeze my pint arm than give them my cash.

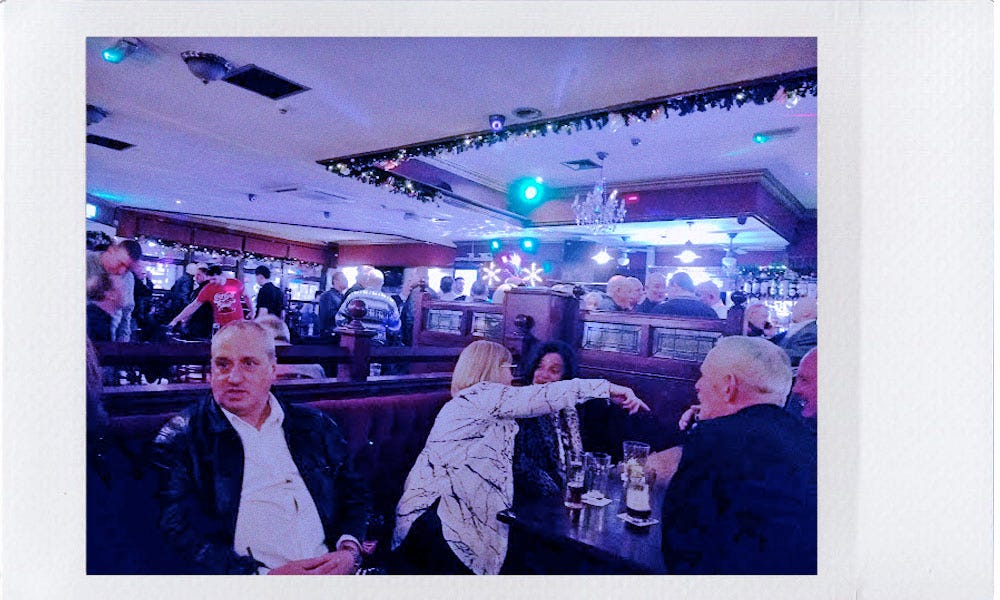

Instead, I head into the cavernous depths of Smokie’s (JR’s as was). Pushing through its doors I do a reverse Narnia, leaving the frigid wastelands behind to soak up the sweet, beer-scented air. Who needs Turkish Delight when you’ve got a creamy pint of Guinness for £3.50?

Booth after booth of old geezers and cheery couples fill the space with a genial buzz. The big tellies are on, showing the darts and the footie, but no-one’s watching. Conversation is the currency here. That is until the turn comes on in an hour, at which point the talk will be of big wheels keepin’ on turnin', and Proud Mary keepin’ on burnin'.

I pull up a chair next to a gang of fellas nursing pints of bitter and lager, and ask what is - to them - the dumbest of openers.

“Why do you come here?”

“Because the beer’s cheap,” they, in beautiful four-part-harmony, reply.

“Where else can you get a pint of Carling for £2.30?” asks one, who turns out to be Charlie, from Tuebrook.

The lads, all in their 70’s, are former Ford factory workers, swapping the Halewood canteen for the reassuring hug of another place where everyone knows their name.

“Don’t take our picture,” Charlie says. “The missus thinks we all go swimming.”

“We’ve been coming here for twenty-odd years,” his friend Fred tells me.

“You have to time it right,” Fred says. “After two at the weekend the prices double when the stag and hen parties arrive. I was at the bar once, and I was three minutes late by the time they’d poured our pints. So we just left them and went up the road to the Midland.”

“We’d have lost touch years ago,” another old fella chips in. “It’s places like this where we can reminisce about the old days. But they’re getting fewer and fewer. Everywhere just caters for the younger ones these days.”

“You should see this street on a Friday or Saturday night,” Charlie says, shaking his head in wonderment. “It’s like Benidorm.”

Above us, Mo Salah slams a penalty kick home in a Man United replay. No-one looks up. The talk is of how to make climbing frames for French beans, and of which leaves make the best leaf mould. (It’s oak and beech, insists Fred, while another reminds the group that azaleas love nothing better than a sprinkle of Christmas tree needles.)

“People worry about community centres and libraries closing down and all that,” Charlie says as I say my goodbyes. “This is our community centre. But who cares about places like these?”

I head next door to Tess Riley’s, but I have to be quick. The staff from the bars along this side of the street are having their Christmas party, so it’s last orders at the bar.

“This is the friendliest place in town,” Jean, from Clubmoor, tells me, finishing off her G&T with her daughter. “It’s a real melting pot, we’ve made some great friends here,” Jean tells me, adding that tomorrow sees the pub host the Tuesday Club – a gang of ex Arriva bus drivers, made homeless after Hockenhall Alley’s Arriva Bus Club was turned into a wine bar. “It’s funny, they always manage to get here on time for that one.”

“Afternoons are the best,” he daughter Emma says. “That’s when you can see the real Liverpool. I have a much better laugh with this lot than any of the younger ones who come in from out of town at the weekend.”

“Well, you can’t talk to them anyway,” her mum says. “They’re too busy taking photies of themselves for social media.”

I trudge over the road to The Blob Shop - Yates’ longest-standing Wine Lodge, set to celebrate its 70th anniversary this year. No one calls it the Blob. Fewer still have even asked for the hot toddy-like concoction it takes its name from.

At the bar, a man tries to scoop up four pints of Strongbow while holding two packets of crisps in his mouth. Armed with recently gleaned knowledge, from Jean, that this street has seen dozens of Britain’s Got Talent singers take to the mic, I’m not sure if this is one of the speciality acts starting early. Another punter looks on, nervously.

“You're not doing dry January this year then, Bob?” he asks.

“Drrrry January?” Bob hisses back through crisp-clenched teeth. “You can gerra cream for that, lad.”

I take my Aussie White and meet Maureen and Andrew, snuggly settled in the bar’s furthest corner.

“We just love it here,” Maureen – originally from Long Lane – says, pouring a bottle of Manns Brown Ale (my Dad’s favourite, I tell her) into a glass.

“We’ve been coming here since the 60s, when there was sawdust on the floor,” Andrew, who’s from Scotland Road, says, as he sips his pint of John Smiths. “It still feels like home to us, and you can’t say that about hardly anywhere nowadays.”

I wonder if they remember the little retaining wall that ran outside the Lodge, lying in wait for hapless punters – like my Dad – to trip them up, and send them flying into the oncoming 544 to Walton Vale? I decide against asking.

“There’s very few places left like this,” Maureen sighs. “All the great pubs around Liverpool are going.”

“Even this place isn’t the same as it was on weekends,” Andrew says, explaining how, since Covid, the little bars of Liverpool have subtly mutated, shifting their focus to attract a younger crowd. The hen parties from Wigan, and the freighted-in football crowds.

These days, Yates’ is an afternoon-only affair for Maureen and Andrew – every Thursday they meet up with the old crowd. “There used to be a big gang of us, but there’s only eight of us left now. We’ve been friends for 60-odd years. We’d go to the pubs along Scottie Road,” Andrew says, “before heading to the British Legion or this place.”

“The acts they had on there were fantastic,” Maureen says. “Mind you, Ruby Blues over the road used to have some smashing singers on, then someone else took it over and it only caters for the young people now.”

Once, Andrew says, there were Wine Lodges scattered across town, from Manchester Street to Lime Street. Safe little harbours of conviviality and conversation. Yates’, for Maureen, may well be their last chance saloon. “When this place goes, we’ll probably stop coming into town,” she says. “It’s not for the old folk like us anymore.”

We talk a lot about community in this city. But as I leave, I think about what Charlie told me in Smokies. These places are every bit as vital as the Kitty’s Laundrettes and the Spellow Lane Hubs; social spaces that knit us together and keep us tethered to the places we love.

The skid row boozers of Great Charlotte Street are not pretty places. You’ll never see them next to The Philharmonic Dining Rooms, or The Vines on the Visit Liverpool site. No one will march to save Tess Riley’s from the wrecking ball; or set up a Gofundme whip round to buy more ale for The Blob Shop. Most of us probably don’t even notice them unless we pass on a weekend and, temporarily thinking we’re in Benidorm, wish we’d taken a different route.

I say my goodbyes to Maureen and Andrew (only after I insist on joining them for a quick half this Thursday, to meet their friends). As I leave, I turn around to wave, but they’ve started chatting to a group of young lads freshly arrived from Lime Street station. I see them as bordering on heroic – although I’m prepared to admit it could be the Aussie White doing its thing – as unassuming protectors of something precious and endangered.

A community, set adrift from the city it once knew, but remaining gloriously, defiantly afloat.

It would have done, I’m sure! If memory serves me right we had but three buses from Northwood, Kirkby. The 544, the 44d and the 92b. Those were long journeys…

I love this! Great article and now I want a characterful local and all my besties there at the same time every week. It’s basically a youth club really, isn’t it?