Our History in Drinks: Liverpool's Shameful Brandy Story

In the first of a series, we look at our city through the blurry lens of booze. First up: brandy, slavery, and an ugly past we need to reconcile with.

Can you put a price on a man’s soul?

You could if you were a Liverpool merchant in the 18th century. And the price was measured in sweet French brandy.

Of all the spirits, Liverpool’s connection to brandy is, perhaps, the most dispiriting. The drink’s inextricably linked to our role in the transatlantic slave trade triangle.

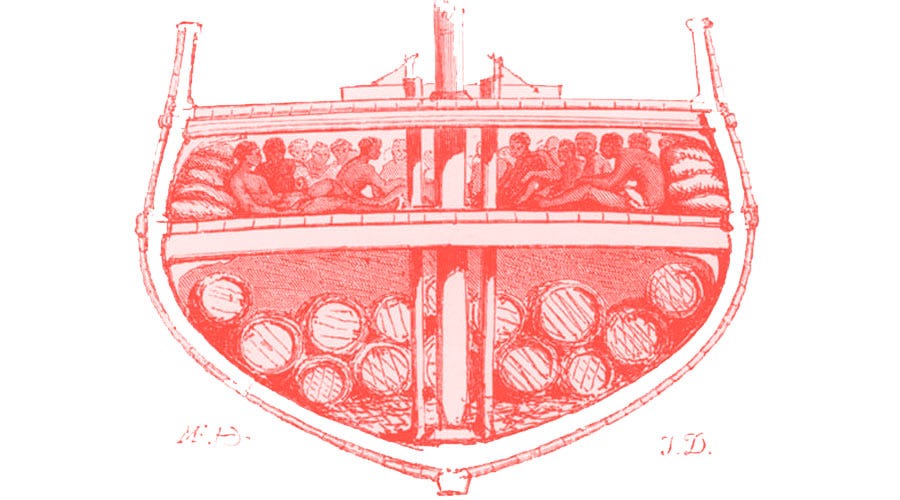

French-distilled brandy, which utilised slave-grown sugar, would be traded in Africa for slaves, to be transported to the Caribbean and the Americas – many of whom were put to work on sugar plantations.

En route, the slave ships would make merry with their sweet cargo during their ten week voyages: captains doling out brandy for crew members on their best behaviour. “A goodly washer woman” would get a flask on a Friday, if she scrubbed the linens especially well.

In his History of the Liverpool Privateers (1897), Gomer Williams reveals that, in 1769, a slave was “worth 6 anchors of brandy” to a trader.

With an anchor the equivalent of between eight and 10 gallons, that puts the price on a slave’s head of 80 gallons. But where could a slave trader lay his hands on brandy, at a good price, for export to the windward coast of Africa?

Step forward Liverpool.

Our city’s merchants were quick to catch on to brandy’s currency: knowledge of what would sell in Africa persuaded many to alter their trade from cotton to fortified wines. Often, to avoid import duty and save a few more pounds, they’d buy illicit, smuggled brandy, in a clandestine trade with the Isle of Man.

In 1765, Liverpool merchants Atherton and Earle petitioned parliament to be allowed to pay a reduced duty on a quantity of brandy imported from the Isle of Man, on the understanding that the drink wasn’t to be consumed here, but for “the African trade only”, they euphemistically phrased it. Sends shivers down the spine, doesn’t it? They imported 20,000 gallons of the stuff. Do the maths.

“The slave trade was not consistently profitable and was very high risk. Liverpool merchants were merchants first, and slave traders second” argues Nottingham University’s Sheryllynne Haggerty, explaining that, for Liverpool, it was all about the secondary benefits the slave trade brought. Not for them the dirty work. They’d stay in their fine city centre villas, counting the cash.

“Whilst Liverpool was vital to the slave trade, it was not equally so for Liverpool. In five years of directories (1766, 1774, 1787, 1796 and 1805), not one merchant listed themselves as a slave trader or slave merchant, despite the fact that many listed themselves as brandy merchants. The slave trade was often simply one part of a merchant’s business portfolio.”

And so it was brandy, imported and exported out of the city, that lubricated the passage of up to six million Africans to the Americas. More than a sobering thought, really.

Long after the slave trade was outlawed, Liverpool still had a taste for brandy. One of the oldest private ship owning firms in the UK, Liverpool’s Harrison Line, chartered ships for wines from France, Spain and Portugal – bypassing the lucrative London brandy trade and setting up direct Liverpool links between distillers and markets, particularly in Brazil. The Liverpool ‘brandy boats’ continued to ply the waters of the north Atlantic until the berthing rights to the brandy trade were finally sold in 1955.

So there you have it. A sordid tale, quite unbefitting of the exquisite nectar. Which is all a bit ironic, when you consider that the spirit started its life, in the 14th century, as a medicine (the water of life - l’eau de vie) doled out by French monks.

Today, the spirit struggles to keep up with its backbar rivals of gin, bourbon and vodka. It takes time to make a good brandy. And there’s a heck of a lot of bad ones out there. But we’d encourage you to go off-grid and try it next time you’re in town. And when you do, raise your glass, and remember how the city first got its taste for Cognac’s golden export.

Where to drink it: Titanic Hotel, Stanley Dock

Try a Hennessy VSOP in the suitably maritime surroundings (and former rum factory) of the Titanic Hotel’s bar. Aged for four years in oak barrels, this is a smooth, fruity and surefire way for the spirit to worm its way into your heart. £8.50

Where to learn more: The International Slavery Museum, Albert Dock

Great read . Thank you.

Ace. Thanks. Just to note: "blurry lense..." should be 'lens' unless, of course, the booze has affected your spelling. Keep up the great work.